Forest Reports

- Biasiolli Forest

- Chestnut Ridge

- Clinch Mountain Preserve

- Edgeworth Forest

- Gill Forest

- Helms Phillips Forest

- Kolb Forest

- Ravens Hill Forest

- Sunshine Forest

2019

Hosting the 2019 owners’ meeting of the 500-Year Forest Foundation was the highlight of the year for the Biasiolli Forest. After gathering for food and conversation at the Ivy Creek Nature Center outside Charlottesville, attendees joined Frank and Eleanor Biasiolli for a hike at their Greene County forest in late March.

September 2014

A note from Frank and Eleanor Biasiolli summarized goings on that contributed “to knowledge about and the health of our forest this year – biotic inventory, stilt grass control effort, deer exclusion fencing, permanent study plots.”

The inventory yielded 231 species, 12 new to Greene County. Unfortunately, one of those is waveyleaf basketgrass. Virginia Forestry and Wildlife Group is working on invasive species removal and on the inventory and plots. That firm’s Brian Morse said “we wrapped up the stiltgrass project for the year. Our team made great progress and covered more of the property than we originally thought.” However, they discovered wavyleaf basketgrass, “a major new threat to Virginia and previously not know from this location (but found in the nearby national park). This sighting has been reported to DCR Natural Heritage. We treated what we found and Frank has since located and treated another patch.”

The deer fencing is set for winter installation, with review requested by easement holder Piedmont Environmental Council. The proposed fencing falls within the forest management parameters already in the easement language and is also part of an invasives control measure recommended by Austin Jamison of Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage. Asked for the best long-range approach, he said the forest needs “a combination of deer exclusion (until an area is re-vegetated) and spraying.” Once leaves are down, Austin will work with Frank on siting the fence.

February 2012

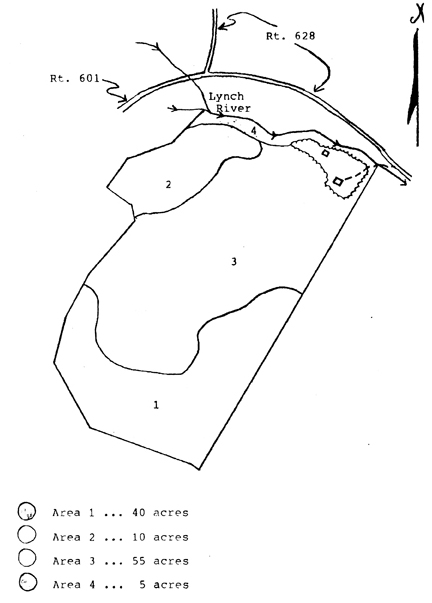

In 1991 Frank and Eleanor Biasiolli purchased 116 acres bounded by the Lynch River on the western border of Greene and Albemarle counties.

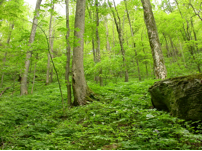

East of Shenandoah National Park’s Ivy Creek overlook, the property is bisected by a small tributary of the Lynch River with two-thirds of the property composed of north facing slopes broken up by small, intermittent streams or seeps which are floristically diverse, with numerous ferns and herbs. Scattered large Sassafras, Yellow Popular, and White Pine, perhaps 100 years old, can be found in the lower section of this area while the ridge tops and higher elevations of the property contain older Chestnut Oak and Black Gum some of which may be as old as 200 year. Since their purchase of the property the Biasiollis have worked to control nonnative invasive plants found on the property and to promote the growth of a diverse, native forest.

Geology

The underlying strata are very old and complicated. Consisting of granite and grandiorite formations, it is a pretty complex composition from the pre-Cambrian times.

Area 1

Area 1 is a large area, 40 acres, at the top of the property. The trees are larger and much older and the logging in the recent past was apparently a light highgrading, removing mostly the larger and more valuable oaks. High up, chestnut oak is now the predominant species, and in places mountain laurel is abundant in the understory. Black gums are also common in the canopy. Many of these trees are well over 100 years old, and some perhaps 200 years or more.

Area 2

Area 2 occupies only 10 acres on a ridge that is very steep on the side sloping to the north, down to the Lynch River. Some of the trees on these steep slopes appear to be very old, some of the chestnut oaks perhaps over 300 years old.

Area 3

Area 3 comprises half of the property and occupies thecentral portion. Most of this area was used for livestockgrazing, and probably even some cultivation in places. The forest now is 30 to 40 years old, with scattered larger, older trees.

There are some beautiful white pines up to 30 inches or so, and scattered, equally large yellow poplar. There is an unusual number of large sassafras, many of these open grown also, some larger than 24 inches. Some of these larger trees are probably 100 years old. The young trees are a mixture of yellow poplar, Virginia and white pines, black locust, basswood, red maple, black birch, hemlock (many of which have been killed by the adelgid), and other species, with a relatively small admixture of oaks. Overall, it is a well stocked and attractive forest. The seeps are floristically diverse, with lots of ferns and herbs. Lush beds of silvery spleenwort (a fern) are especially attractive, and golden ragwort was blooming abundantly in some seeps.

Invasive Plants

Invasive plants are a problem, especially on the moister sites. Oriental bittersweet, barberry, Japanese stiltgrass, and garlic mustard presently appear to pose the biggest problem, and it will be difficult to keep them under control without help.

2019

Continuing efforts started in 2018, board chair David Ledbetter worked with the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation in its bid to secure funding to purchase the Chestnut Ridge Natural Area Preserve/500-Year Forest and additional adjoining forest lands owned by Bob and Darlinda Gilvary.

2014

Sharing responsibility for Chestnut Ridge Preserve continues to reap benefits for the Foundation from its cooperative agreement with the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation in monitoring the forest’s conservation.

Natural Heritage staffers visited Chestnut Ridge late last year and provided the Foundation with updates. Similarly, a request in the summer of 2014 from Radford University researcher Stockton Maxwell (now a 500YFF scientific advisor) to do tree ring work in the Chestnut Ridge forest was forwarded to DCR. The collaborative relationship was further deepened by Foundation inclusion in an arrangement to share easement monitoring funds and in the DCR’s 2014 survey of conservation activity.

Fall 2013

Virginia’s Natural Heritage Program, a partner in protecting this forest, spent two days there on a monitoring visit in September. The Foundation expects to receive a report on the visit in early 2014 from Natural Heritage staffers Larry Smith and Irvine Wilson. The two share forest owner Bob Gilvary’s concerns regarding a proposed wind farm project. Bob has received a map from Dominion Power suggesting direct impacts to the 500-Year Forest natural area preserve. Natural Heritage has contacted the power company for a meeting to learn more about the project and share information with them about the restrictions over the tract and the sensitivities of the property.

June 2012

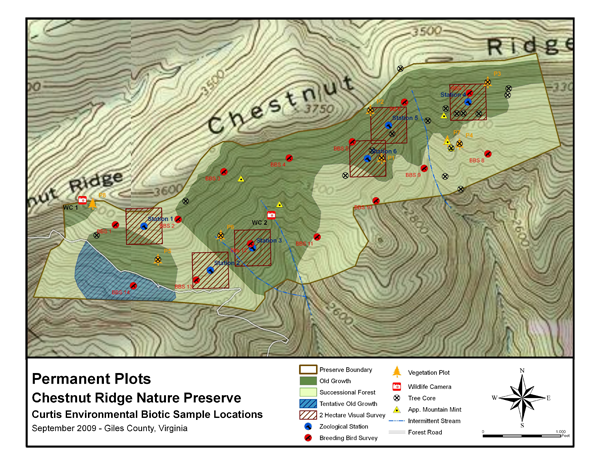

This 500-Year Forest is also one the Virginia’s Natural Area Preserves. Two years ago the 500-Year Forest Foundation hired the Curtis Environmental to perform the Biotic Inventory for this forest. The Natural Heritage Division of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, as represented by Ryan Klopf, Mountain Region Steward, is in the process of creating a management plan, which should be ready by the year’s end for this forest.

November 2010

The biotic inventory has recently been completed. The Virginia Natural Heritage will now develop a forest management plan.

In the interest of determining carbon credits for his 2500 acre forest, Bob Gilvary hired Britt Boucher of Foresters, Inc. to compute the annual carbon storage capacity of 15 stands in his forest. This old-growth stand was calculated to be removing 3.87 tons of CO2 per acre annually, an amount equal to slightly more than a ton of carbon per acre.

June 2010

The results of the Chestnut Ridge Natural Area Preserve spring biotic inventory conducted May 9-12 by Shay Garriock uncovered two rare animal species: a green salamander (Aneides aeneus) and a singing male Blackburnian warbler (Dendroica fusca). The Green salamander was found in a damp rock crevice just below the ridgeline in the north central property region. This species is listed by the VA Natural Heritage Program as S3, which means that it is rare to uncommon in Virginia with between 20 and 100 occurrences. The Blackburnian warbler is listed by the VA Natural Heritage Program as S2B, which means that breeding occurrences are “very rare and imperiled with 6 to 20 occurrences or few remaining individuals in Virginia”. The Blackburnian warblers are establishing territories on the property.

November 2009

In three-day sampling and observation periods this past June and again in September, Kevin Caldwell, botanist, identified 186 species of trees, shrubs, vines, herbs, grasses, and sedges. Shay Garriock, zoologist, identified 62 species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians, and 38 species of butterflies and moths. These numbers will likely grow significantly when moth identification is completed over the winter and the third and final inventory is taken in April or May of next year.

Results still to be analyzed from trees corings will more firmly establish the extent of both the original forest and successional forest. Community designations, e.g. Basic Oak-Hickory Forest, will be defined after the spring inventory.

Two Watch List identified plants include Mountain Pimpernel and Butternut. Only five invasive species were identified. The worst is confined to one small previously disturbed part of the forest. Control should not present a problem.

As usual, the best plans for identifying species can be foiled. Two wildlife cameras had been pulled off their mounting trees by black bears that didn’t seem to want their picture taken. But, before that, a bear, a bobcat and an opossum posed for a photo.

May 2009

We have hired Curtis Environmental of Pittsboro, NC to do the biological inventory in the Chestnut Ridge Natural Area Preserve. Shay Garriock, zoologist, and Kevin Caldwell, botanist, will team up to do this study. The process will bring these two men into the forest for three individual three-day periods during the growing season. Their first effort will begin this summer and the second effort will take place in the fall. The project will be completed next spring. Their final report will be sent to us and the Natural Heritage Division of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. The Natural Heritage Division will prepare a management plan for this very special forest.

The proposed inventory, using both qualitative and repeatable, quantitative methods, will sample vascular flora and vertebrate faunal groups. The survey will serve as a baseline biological inventory showing existing conditions. Permanent inventory plots set up for the survey will provide opportunities to measure changes in the forest over time. The inventory will also identify and map unique habitats, natural communities, rare species locations, water resources, and threats to forest health from invasive and pest species.

November 2008

Bob Gilvary has become interested in generating carbon credits from his 2550 acre tree farm which includes 232 acre 500-year forest nature preserve. This spring he hired Britt Boucher of Foresters, Inc. to measure his forest for this program. Britt commented that this “place has the least amount of invasives of any property I have been on.” There was no Ailanthus (Tree of Heaven or Paradise), only one barberry plant, a few multi flora rose plants and some “garlic mustard at the lowest landing but no place else.

May 2008

Bob Gilvary reported that plans have been delayed to put the remaining 2,236 acres of the Gilginia Tree Farm under a conservation easement until it is determined whether it is possible to do this and still have a wind farm on the property.

Bob reports further that he has signed up for a carbon sequestration program on the entire 2,550 acres. At present forest growth rates about 94,000 tons of CO2 could be sequestered per year. The present plan is not to cut any timber on the property for at least ten years to let the large oaks mature more and thus sequester more carbon. In the meantime timber stand improvement will continue to increase growth rates.

According to Chris Ludwig, Chief Biologist, Virginia Natural Heritage Division, the state will do a one day inventory this fall looking for rare forest types located outside but nearby the existing 233 acre preserve.

October 2007

For Bob and Darlinda Gilvary extreme drought and the threat of gypsy moth invasion made for a harrowing time this summer. Relief from the drought finally occurred in late October with five plus inches of rain that fell over three days. The gypsy moth was a problem in eastern Giles County and there was a concern that it would travel into western Giles County where this forest is located. Since this forest is one of the Virginia’s 50 Natural Area Preserves, the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation arranges for any control efforts. Bryan Wender, Mountain Region Natural Area Steward, inspected this old-growth forest and found no evidence of gypsy moth.

April 2007

Boundary signs including the identification of both the Department of Conservation and Recreation and The 500-Year Forest Foundation have been installed every 300 feet around this old-growth tract with blaze markings every 100 feet. The state hired Thompson & Litton, surveyors to do this work. Recently Al Cire, Western Operations Steward with the Department of Conservation and Recreation, inspected the completed work and said the job was well done.

Late 2005–2006

In December 2005 Britt Boucher of Foresters, Inc., Blacksburg, appraised the stumpage value of the 233+ acres of forest at $440,000. (Stumpage value is the value of lumber that can be sawed out, minus the costs of harvest, transport, and conversion to lumber including a margin of profit.) There is virgin timber (never been cut) on about two thirds of the land.

In March 2006 Mathews and Henegar, Inc. of Dublin, Virginia completed a survey of the property. The appraisal of the forest land both before and after development and timber rights is called the easement value. Randi Lemmon of Lucas Real Estate Appraisers, Inc. of Blacksburg performed this easement valuation, arriving at a figure of $538,000. The coverage for the required 50% match to the grant was more than adequate.

The Commonwealth of Virginia in the Department of Conservation and Recreation prepared the Deed of Natural Area Preservation Dedication. When all grant requirements were met, the deed was signed and disbursement was accomplished August 29, 2006.

June 2005

In June 2005 The 500-Year Forest Foundation was awarded $224,130 from the Virginia Land Conservation Fund to purchase 50% of the development rights ($200,000) of the forest to be offset by at least a 50% donation by the Gilvarys. $24,130 was budgeted to pay for appraisals, survey and legal expenses. The actual costs of these services were less than $11,000. The DCR , the Gilvarys, and The 500-Year Forest Foundation will develop a Natural Areas conservation plan for the forest.

Fall 2004 and Spring 2005

In the fall of 2004 a visit by Philip Coulling, vegetation ecologist, with the Natural Heritage Division of the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) determined the importance of the site. The forest “supports two significant communities (northern red oak and chestnut oak) noteworthy for their old-growth status. In addition these communities occur in a large matrix of nearly unbroken forest, the extent of which is quite unusual in southwest Virginia.” Another visit in spring of 2005 by a team of VNHP scientists confirmed the existence of trees that were from 300 to 400 years old. Other canopy species in the forest with aged individuals include cucumber magnolia and American basswood.

2019

Clinch Mountain Preserve continued to benefit from regional conservation efforts by The Clinch Coalition. In 2019, the organization addressed ATV trails that threaten environmentally sensitive waterways and responded to proposed logging in areas nearby Clinch Mountain 500-Year Forest. As associate director, Steve Brooks continued his long-time affiliation with The Clinch Coalition.

October 2014

New director Jeff Smith proposed a forest owners meeting for 2015 that coincided with ephemerals season at Clinch Mountain Preserve. Owners Steve Brooks and Maxine Kenney agreed to start conversations with Jeff about a walk in their woods for fellow 500-Year Forest owners.

Fall 2013

The never-ending efforts to eradicate invasives led to a discussion at the October forest owners luncheon of a fungus that kills Japanese stilt grass. However, forest owner Steve Brooks who made the presentation had to conclude that it’s not as yet a meaningful option in battling the invasive. Similarly, a report in the Foundation newsletter of damage to large trees by wild grapevines prompted an email exchange on the virtues of swinging on vines. Steve said he could safely promise that he wouldn’t eliminate them all. This forest also reported discovery of a huge, 50-pound Hen of the Woods polypore. The owners are also beginning their readiness for a revisit of biotic inventory plots.

June 2012

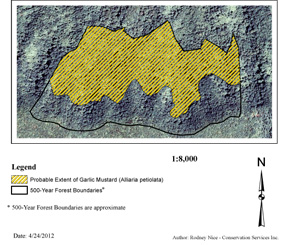

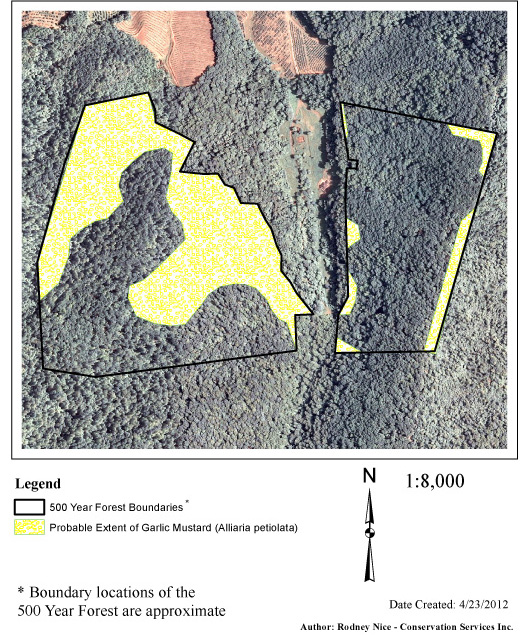

Probable or Known Extent of Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) infestation across the Clinch Mountain 500-Year Forest

Map showing probable extent of Garlic Mustard

The recent study conducted this spring by Rodney Nice identified Garlic Mustard as a serious threat to the under growth of the forest through much of this forest. See the accompanying chart. Hopefully a program can be designed to stall the Garlic Mustard’s advance upwards in the forest without affecting the pristine streams that flow on the property. To a much lesser degree, three other invasive plants of concern are Japanese Stilt Grass, Ailanthus, and Multiflora Rose.

November 2010

Japanese stilt grass on the Run by Maxine Kenny

Now that summer is only a memory we have time to reflect on our continuing struggle to combat garlic mustard, ailanthus and Japanese stilt grass – three of the most tenacious invasives on the Clinch Mountain Preserve’s 500-Year Forest. Fortunately for us we had the assistance of two young, energetic Eagle Scouts who pulled great patches of garlic mustard in the spring. One of the teenagers came back during the summer to help us stalk and destroy a great many ailanthus trees and saplings.

In an unexpected turn of events, nature itself may have set us on a path of biological elimination of the stilt grass that has swept across our lower acreage and along pathways that lead into our 500-Year Forest on the upper slopes of the Clinch Mountain. In early July a forester friend, Russ Richardson, told us about a fungus called Bipolaris that he thought was killing stilt grass on his West Virginia farm. He sent pictures to us of stilt grass that had brown lesions on its leaves and shared an academic paper regarding the phenomenon written by a biologist at Indiana University. Later in July, during a hiking trip to the Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve in southwest Virginia, we saw stilt grass along the hiking trails that appeared to be afflicted with the same brown lesions. Subsequently, that sample was confirmed as infected by Bipolaris fungus.

Soon after we saw what we believed to be Bipolaris lesions on the stilt grass along our own driveway. We sent it off to be analyzed and it too was confirmed as Bipolaris. We checked back with Russ in West Virginia to discuss the infestation on our property and he said that the fungus spreads in much the same way as stilt grass itself – that is, it rides along pathways traveled by both humans and animals – so he wasn’t surprised that after we waded through infected stilt grass at the Pinnacle that it had hitchhiked back home with us on our trouser legs. He also told us that much of the thriving stilt grass that he observed on his property last year was now reduced to a dead, dry thatch! Wouldn’t it be wonderful if nature could rid our fields and forests of stilt grass.

June 2010

Over the last several years Steve Brooks and Maxine Kenny have had a tough time finding help to tend to invasive control in their Clinch Mountain Preserve. Garlic mustard control was to be the focus this spring. The worker who was lined up came just two times. Now it appears that two local boy scouts, one an Eagle and one a Life scout, may be able to help during the summer time. Their effort will be focused on stilt grass and ailanthus control.

November 2008

There are pathways of Japanese stilt grass leading up the mountain from the lower acreage to the 500-Year Forest. Steve and Maxine assume the stilt grass seed is being transported into the Forest along the footpaths by both wildlife and hikers. They plan in the spring to experiment with a flame weeder to knock back stilt grass along the roadways and paths leading into the Forest. At the same time they plan to contract with a local landscaping service to hand pull stilt grass during June and August in specified areas in our Forest.

May 2008

It remains dry here on the Clinch Mountain in far Southwest Virginia! Though the year started out with adequate rain fall, most of the rain passes to the west and north of Scott County. We are now over 3 inches below the normal level for this date! Last year we only received half our normal rain fall and a late freeze was disastrous. Some tree species, spring flowers, and much of our fruit was damaged. (We lost 90% of our blueberries in 2007.

The huge box elder trees that flourish in the lower sections of our property (not in the 500-year forest) seem to have been hurt the most. Many branches lost their leaves last year, thus producing dead limbs which make for precarious situations near our house and farm buildings.

Damage to trees at higher elevations is not as noticeable, especially the old trees which are well rooted. However this may change if the drought continues as we understand it usually takes 2 or 3 years for it to affect most trees.

The invasive plants, such as the garlic mustard, seem to thrive under this climatic stress and its growth may even have been stimulated. It is back in full force this spring. It appears to be most prevalent in the valleys where it is less dry and has spread both up and down the hollers from the trails that run through them. With the help of Dale Fields we have been able to remove a large number of these plants in the Old Growth section of the property. Dale has spent three days pulling and piling the plants in areas where they were most abundant. Though the plants have finished blooming they will not go to seed for some time yet, so Dale will continue to pull them as time allows.

Our mountain springs continue to flow! For that we are thankful. All the water coming to our house is gravity fed and the springs are high enough above us to provide the necessary 40 lbs of pressure. We have the sweetest, purist drinking water available anywhere. Because trees have not been cut on our part of the Clinch Mountain for many years we believe the springs will continue to flow much longer than on other properties where major cutting has taken place. If the drought does continue we may soon be providing water to our neighbors and friends. Last summer many shallow wells and non-forested springs in our region went dry.

October 2007

Two work projects were identified from the inventory work of Anna Hess, Field Biologist. They are aimed at controlling invasive plants and at clearing a narrow footpath that will provide the necessary access to the property. Along with Steve and Maxine we have hired Dale Fields to undertake this program of work. The Foundation will pay Dale for his work in the forest

The invasive plants in this forest are a minor problem compared to many forests and for the most part these plants are in the lower northern section of the forest. Dale, under Steve’s leadership, spent several days working on the control of Japanese Stilt Grass and Ailanthus. Our first effort to begin garlic mustard control is planned for the early spring.

Steve and Dale marked the lower boundary of the forest which is along the 2,100 foot elevation contour. A path will generally follow this contour.

Jan.-April 2007

April 2007

Anna Hess, Field Biologist, has completed her field work and provided two reports: Inventory of the Brooks-Kenny Tract and Plant Community Analysis of the Brooks-Kenny Tract. This work establishes important forest baseline data. We can now trace the health of the forest, monitor plants with special attention to the six rare species, and provide knowledge to manage the forest appropriately.</p>\r\n<p>Three main forest community types make up the Brooks-Kenny tract: Community I is a relatively young Yellow Buckeye-Yellow Poplar-White Basswood forest found in the northwestern part of the property and in old tree fall gaps. Community II is a Sugar Maple-White Basswood-Yellow Buckeye forest which was found in the northern and central portions of the 500-Year Forest Foundation tract. Community III is a Chesnut Oak-Sugar Maple-Northern Red Oak forest found on the crest of the Clinch Mountain and on its descending ridges.

January 2007

The extensive field work of Anna Hess, Field Biologist, resulted in her written report backed-up by computer files with all the data she had collected over 28 site visits from March to November 2006. She established 32 circular permanent plots randomly spaced through the forest with four smaller herb plots within each of the larger plots. Emphasis was placed on an inventory of trees, flowering plant and ferns. We are reviewing the draft of the report currently.

Fortunately the bulk of the invasives species are on the land below the 500-year forest. They are beginning to creep into the forest. A plan is being developed to control the spread of the invasives.

Mar.–Nov. 2006

Anna Hess, Field Biologist, completed an inventory of plants and animals in the forest during 2006. A management plan has been prepared using this information. In the spring there was a great profusion of wild flowers in the coves. Johnny Townsend of the Division of Natural Heritage was very helpful in species identification. Within the forested area the variety of plants and animals are very diverse. The 195 species include:

6 rare plants

15 invasive plants

8 amphibians: 2 frogs and 6 salamanders

A number of neo-tropical birds including 1 that was rare

1 rare butterfly

0 invasive animal species

June 2012

Probable or Known Extent of Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) infestation across the Clinch Mountain 500-Year Forest

Map showing probable extent of Garlic Mustard

The recent study conducted this spring by Rodney Nice identified Garlic Mustard as a serious threat to the under growth of the forest through much of this forest. See the accompanying chart. Hopefully a program can be designed to stall the Garlic Mustard’s advance upwards in the forest without affecting the pristine streams that flow on the property. To a much lesser degree, three other invasive plants of concern are Japanese Stilt Grass, Ailanthus, and Multiflora Rose.

2019

In June, students from Randolph College conducted an inventory of the property with guidance from their professor, Karin Warren, a 500-Year Forest Foundation director. The inventory work was underwritten by a Randolph College grant. As Karin wrote in the grant proposal, “Each inventory will include tree density, species (native and non-native), abundance of coarse woody debris, scrub, and herbaceous species, diameter, average stand age, and observation/assessment of human disturbance.”

2019

In early January, Foundation board members David Ledbetter, Hullie Moore, Karin Warren and Ches Goodall visited the Gill Family Farm to assess potential for its 365 forested acres as a 500-Year Forest. Met by owner Charles Gill and “caretakers” Suzie and Maggie (see photo of family dogs), the board found impressive specimen like the one Hullie photographed David standing near. Following subsequent unanimous approval by the full board, the easement making the 500-Year Forest Foundation a conservation partner was recorded on Christmas Eve.

2019

In late winter and early spring, a two-man crew helped clear detritus from the November 2018 ice storm that was impeding some forest edge maintenance, allowing regrowth of ailanthus and other invasive species. Later in the year, the Virginia Outdoors Foundation sent a staffer out for routine compliance monitoring of the conservation easement parameters, reverting to in-person visits again instead of written questions.

Summer/Fall 2014

With continued support from the Ecology Wildlife Foundation to eradicate invasive species, Austin Jamison of Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage went into the Helms Phillips Forest to tackle garlic mustard and Japanese stilt grass. The garlic mustard effort also let the Foundation for the first time use a Master Naturalist volunteer to audit the work. In his Master Naturalist capacity, former program director Jeff Smith who has subsequently joined the board, visited the Helms Phillips forest.

Jeff’s July 2014 garlic mustard report read: “I surveyed the spray areas as noted in the map provided. In general, the garlic mustard was mostly gone from the areas. It is, however, not eradicated as my finds will show. I do believe, however, the spraying has made a huge impact in that my sightings were of singular plants or a very minor incursion of multiple plants (maybe 2 to 4). As an aside, stilt grass is quite noticeable on the top ridge along the trail.

Austin took aim at the remainder of the garlic mustard on a subsequent spraying visit. “I also found some very small ailanthus on the ridge today and sprayed what I found,” Austin said. He proposed treating the areas for 2 more years, once each April and June, to really get them under control

Rick Helms continued work on ailanthus eradication with the help of independent contractors Kris Smith and Joe Huber. Much of the effort involved clearing fallen trees from previous poisoning sessions.

Fall 2013

Former Foundation director Nancy Weiss recommended Austin Jamison, a Habitat Coordinator with Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, for forest work. He has met with Foundation officers and visited the Helms Phillips forest twice. He is taking aim at garlic mustard during the winter of 2013-2014 and his efforts are paid for 100% by the Foundation under its Ecology Wildlife Foundation grant invasives initiative. The forest owners have also used matching grant monies from the Foundation to hire help to clear fallen ailanthus trees from the meadow-forest perimeter. Nancy and Carol Wise visited the forest as a volunteer easement monitors for the Virginia Outdoors Foundation in December 2013. They were welcomed by the Foundation’s new Member Forest sign (and family dog Uno).

June 2012

Probable or Known Extent of Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) infestation across the Helms-Phillips 500-Year Forest

We hired Rodney Nice to give us a picture of the invasive plants in this forest. His report and management plan is focused on identifying and controlling unwanted invasive plant species. Native and non-native invasive species are a common site across the Helms Phillips property. These include such species as: Japanese Stiltgrass, Garlic Mustard, Royal Paulownia, Tree-of-Heaven, Japanese Barberry, Multiflora Rose, Oriental Bittersweet, and Devil’s Walking Stick. The report detailed control measures for these invasive plant species. See the accompanying chart for the range of Garlic Mustard. Rick Helms has begun implementing the recommendations.

December 2010

For two years in the late 1990’s, Rick and Carolyn traveled the back roads in Albemarle County looking for their special place. In 1999 they found a lovely and unusual site of 206.5 acres south of Batesville in the upper end of “Big Spring Valley”. Their lower valley, at one time an apple orchard, is defined by Castle Rock Mountain on the west and Long Arm Mountain on the east

The largest area of forest lies on the north-eastern flank of Castle Rock Mountain. It covers about 105 acres and is composed of hardwoods, aged between 65 and 85 years. There are three coves with streams flowing into Whiteside Branch. Another section of about 54 acres lies on the western slope of Long Arm Mountain. This forest stand is 90 to 120 years old with some trees measuring 40 inches in diameter at breast height. The three most prevalent species in both stands are chestnut oak, yellow poplar, and northern red oak. A third section, 47.5 acres, of this property was an apple orchard and is now a young forest. This young forest is being excluded from the 500-Year Forest.

Rick Helms and Carolyn Phillips placed their property under a conservation easement in December, 2005 with the Virginia Outdoors Foundation. This easement has been modified with language from the 500-Year Forest Foundation. They have given up the right to harvest any timber in the 500-Year Forest, and to further sub divide the property in any way. This transaction was consummated in the fall of 2010.

Year Long 2019

Summer rain was, like last year, a prominent factor in our forest’s activity. Tree trunks no doubt added a wide ring, and branches produced more foliage than we’ve ever seen. By November, fallen leaves lay thick all over the forest floor, completely hiding the single, overwintering leaf of a number of cranefly orchids I know about. I uncovered them. Winter winds usually shift fallen leaves—thinning here, piling there—so maybe they’ll be more spread out by April.

Canopy gaps made by the November 2018 ice storm now have grasses and forbs around the big oak and hickory trunks that were felled while their ice-collecting leaves were still attached. Hundreds of broken-off branches, including some beech tree tops, are still visible in the forest. The rain increased two native forest grasses (Brachyelytrum erectum and Muhlenbergia sobolifera). They’ve been around sparingly for years, but this year they multiplied vigorously.

It was unusual for mosses to stay green nearly all summer. Their one-cell thick leaves must be moist for photosynthesis to take place, and our north-facing slopes helped them retain water. We have quite a variety—some suggesting ferns, vines, hemlock branches, cushions, pines, or golden-green fur and others I don’t have descriptive words for. They are a widespread part of our forest.

Stilt grass, of course, enjoyed the rain, which reduced spraying days, but Leif Riddervold’s crew resprayed last year’s areas, limiting next year’s seed production. Some sprayed areas now have no stilt grass; some retain plants here and there, which—having no competition from siblings—grow large, no doubt making plenty of seeds.

There’s always something. I spent many hours spraying clethodim on isolated patches myself. Clethodim only kills grass, so stilt grass in a clump of ferns no longer requires tedious hand-pulling, but stilt grass among native grasses does. Leif’s crew sprayed the few Wavy-leaf basket grass plants, and I hope got them all. We may need Riddervold’s help again next year.

Will Allen from VanYahres Tree Service inoculated four of our few white ash trees on the mountainside against the Emerald Ash Borer. Others did not look good. (The next threat to Eastern trees appears to be the Spotted Lanternfly recently observed in Virginia.) Shirley Halladay helped me pull invasives on lower slopes; Peter Mehring removed stilt grass and garlic mustard along a stream and on higher slopes, and cut bittersweet vines everywhere. Large bittersweet vines in our forest are a thing of the past, but small ones yearning to climb show up because birds eat the orange fruits from vines on an adjacent property, sit in our trees, and conveniently poop undigested seeds onto the ground around a trunk.

Female persimmon trees are now loaded with fruit that falls intermittently into the winter—food for deer and raccoons among others. Spicebush produced many berries, which were all gone before a late flock of robins arrived looking for them. Bears were busy overturning rocks—some really big ones—to get the edibles underneath. They left other sign—bear tracks on our deck and scat elsewhere—but the bears themselves stayed out of sight. All told, 2019 was a good year. Rain is always better than drought.

Year Long 2018

With 71.57 inches of rain this year, our forest trees not only increased in diameter and height, they added a lot of new branches, lengthened old ones, and produced a super-abundance of foliage. Beeches shot up taller and spread their lower branches wider, more tulip trees are now over 36 inches DBH, and an unusual number of slippery elm seedlings appeared.

A downside of all that growth came with the ice-storm of 15 November. Longer branches collect more ice, and many came down, especially from tulip trees and maples. Oaks and hickories—still holding most of their ice-collecting leaves—were hard hit. Up on the mountainside, a giant northern red oak (estimated diameter: 39 inches) that was likely over 100 years old crashed down and took a large basswood with it. Fortunately, our largest butternut (63 cm DBH) was not damaged.

I suppose ice is a natural thinner of forests, but it’s a rough method—hard on the trees and hard on the two-legged mammals that live in the forest and have to deal with the damage. Back in July, a major wind storm laid eight good-sized sassafras trees and a black locust across our through-the-woods driveway, but its abuse was less widespread than the ice storm’s.

The forest got some help in July from Virginia Forestry and Wildlife Group. A team sprayed our stilt grass for a second year. The biggest areas of stilt have been seriously knocked down but aren’t entirely out. Unfortunately, the abundant rain helped stragglers survive and prosper. I did a lot of spray-bottle, spot zapping with glyphosate and, toward the end of the summer, used clethodim since it only kills grasses. I hope to do that again next summer, but we still need help on the large areas. Alas, the battle against stilt grass goes on—and on.

Spring rains produced more wild flowers than usual. Over a hundred small Turk’s-cap lily plants appeared on one slope, but none made it to adulthood—deer, no doubt. The only ones that grow tall enough to bloom are within our fenced area that protects them and other species that deer love. Within that fence, 255 bloodroots bloomed in March, hundreds of pink wild

geraniums followed in May, and over the rest of the summer goat’s-beard (Aruncus dioicus), lopseed, turtle-head, Turk’s-cap lily, wild hydrangea, and others flowered. In June, a pair of hooded warblers built a nest and reared young in one of the bushy wild hydrangeas. These plants, and many others, still try to bloom in the forest, but are much eaten by deer.

Of the eleven naturally occurring orchids I’ve seen here over the last 40 years, I spotted nine in 2018 as I searched for stilt grass: puttyroot, showy orchis, spring coralroot, autumn coralroot, downy rattlesnake-plantain, lily-leaved twayblade, cranefly orchid, and nodding ladies’-tresses. I didn’t find green adder’s mouth or bog twayblade again, but I did, for the first time, come upon a handsome, 16-inch tall slender ladies’-tresses.†

Fungi flourished in the rains and brought out an astonishing variety of fruiting bodies —from “mushrooms” of many sizes and colors to the unusually abundant white fingers of coral fungus. Mosses—already numerous in our north-facing mountainside—expanded their holdings and were richly green all year. But there seemed to be fewer bees, wasps, and yellow jackets, perhaps from ongoing rain. I also saw fewer migrating birds in the fall, although a small flock of robins passed through. There have, however, been more signs of bear presence: large piles of scat, rotting logs pulverized, and muddy bear tracks several times on our deck, possibly those of the very large bear who casually walked by our house early one morning.

In October, before hunting season opened, we confronted five or six bear hunters, without guns but with 24 large dogs that were leaping and barking at the base of a tall tulip tree at whose top we could see a frightened black bear. The place wasn’t far up the mountain. The men insisted that they had a right to “retrieve” their dogs; we told them politely but firmly that we didn’t want them on our posted property. It took some time but they finally gathered up all the barking, excited dogs, leashed them, and pulled them off around the ridge and out of sight. We waited until they had left, to be sure the bear could come down safely. We haven’t heard the dogs again. A neighbor says someone is baiting bears not far away from his property.

Tom Dierauf tells us that “a forest is always changing,” and there were certainly changes this year—some for the better, some for the worse. We hope the increasing size of most trees makes up for damage others suffered from wind and ice.

†Orchids in the order listed are Aplectrum hyemale, Galearis spectabilis, Corallorhiza wisteriana, Corallorhiza odontorhiza, Goodyera pubescens, Liparis liliifolia, Tipularia discolor, Spiranthes cernua (I think); Malaxis unifolia, Liparis loeselii; and Spiranthes lucera. Fine color photographs of all of these are in Stanley Bentley’s Native Orchids of the Southern Appalachian Mountains, University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Fall 2013

Just before hosting visitors during the Foundation’s annual meeting day in October, the owners finished a new Two Bridge Trail. Also, they added a fifth bridge to their network. This one takes hikers across a ravine carved out by Hurricane Camille. With substantial paid staff hired with an assist from the Foundation, all trails were cleared from water, storm, wind, snow, and electric company damage. But such tasks never stop. Soon after the clean-up, a large tree came down on the Ridge Trail ten seconds after Jean Kolb passed by it. An unusual summer (July had nine inches of rain and cool weather) contributed even more to the never-ending challenge of war against invasives.

June 2012

As owners of a 500-Year Forest for almost eight years now, Hal and Jean can see real progress in their invasive efforts. This year they added 4th year student Michael Jordan to their crew of occasional workers with Peter Mehring, Lee & Kathryn Kolb, Shirley Halliday (reimbursed with firewood), and Ryan Mehring (compensated by University of Virginia’s charity day program). In addition to the routine invasive work done by all, Michael helped with clearing under the electric line and building the new Taylor Creek loop trail.

November 2012

When a storm takes down a good-sized tree in our forest, it slowly becomes a food bar for bears—a rotting log offering grubs, ant larvae, termites, and perhaps a mouse nest or seed cache. Pulled-off chunks of softened wood mark a bear’s visit. A pile of large splinters beside a less decayed log is the work of a pileated woodpecker with similar intent. This year, I found wild turkey droppings and a feather among hundreds of discarded burrs under a nut-loaded chinquapin and empty shreds of chewed-open acorns under the chestnut oaks. Gray squirrels husked and planted the black walnuts they didn’t eat, and although chipmunks and birds harvested most of the spice bush berries, we found several small caches of bright red berries stored by an Allegheny woodrat. Orange persimmons adorning leafless female persimmon trees will drop now and then for weeks, extending the fall food supply, while clusters of wild grapes, blue greenbriar berries, and white poison ivy berries (enjoyed by woodpeckers) will be available through most of the winter.

With an eye on future mast production, we distributed sprouting white oak acorns provided by Peter Mehring. To keep antlers away from a beautiful, straight American chestnut—35 feet tall, 4 inches in diameter in a canopy gap—we caged its trunk and hope it lives to produce chestnuts. Beech trees, recent additions in our forest, have pushed their shade tolerant tops 30 feet toward the canopy; when about 40 years old, they should begin adding beechnuts to the wildlife food supply.

To be sure, we’ve continued to attack non-native invasive bittersweet, garlic mustard, ailanthus, and stilt grass, because, if invasives take over, there’ll be much less food for wildlife.

June 2010

This beautiful stream in the Kolb 500-Year Forest is flush with melting snow and rainfall. Hal Kolb says, “There is nothing prettier that a stream running through a forest. It seems to me that one of the great contributions of a mature forest is to store water for slow release and botanical nourishment.”

Hal and Jean Kolb are so fortunate to have Peter Mehring continue to help them with invasive control in their forest. In April and May he has divided his working time between oriental bittersweet and garlic mustard. It should be said that Hal and especially Jean spend many hours in their forest removing the noxious plants.

October 2009

In late October, four 500-Year Forest Foundation directors visited the Kolb Forest where they saw some large tulip trees and heard Jean Kolb talk about removing non-native invasive Japanese stilt grass, Microstegium vimineum. Stilt grass, she explained, can grow three feet tall and fall sideways, which puts its top-growing seeds several feet beyond the mother plant, and advances its spread. If seeds have not formed, they pull the grass and hang it in bunches above ground; if seeds have formed inside the stem tip, they bag the plants and pile them in Jean\'s fenced garden to be monitored. "It's amazing to me," Jean says, "that we can actually win this battle.

November 2008

By Jean Kolb

Our attack on non-native invasive plants continues. I checked all the old garlic mustard sites--already marked with orange surveyor’s tape--for new plants and either pulled or squirted them with Roundup. As I pursued garlic mustard and any remaining mile-a-minute, Peter Mehring cut bittersweet vines and treated their cut surfaces with Roundup to kill the roots. We cleared Bristled Knotweed, Polygonum cespitosum, from trails where it was being tracked in both directions and, as stilt grass grew more visible, we put our efforts into pulling it--in a few cases, spraying it. When a split-stem end showed tiny seed development, we bagged our pulled plants and safely cached them inside my garden fence. We made major progress in clearing many sites, and next year we’ll see how thorough we were. Stilt grass patches that have been pulled for two years in succession produced only a few plants this year, and most patches pulled for three years have disappeared.

May 2008

Non-native invasive plants coming into the forest from adjacent properties present an ongoing problem. Birds and animals disseminate seeds of invasive as well as other plants over the areas of their territory which of course do not correspond to human property lines.

Thus, the battle to control invasive plants takes continual effort. Over the years Jean Kolb has worked diligently to control garlic mustard. Her efforts have been successful in removing it from many areas and greatly limiting its spread in others.

With serious help from the Mehrings, Peter and sons, Adam and Ryan, oriental bittersweet is beginning to be reigned in. Although Japanese stilt grass has been cleared from several small areas and reduced in some others, it remains a major problem. Areas infested with mile-a-minute vines are relatively small and will be attacked in the coming weeks.

Of the many flowering plants in the Kolb forest, some have been so heavily browsed by deer that the Kolbs have fenced in an area 65 by 85 feet to protect the deer-favored species such as the ones pictured here.

October 2007

This has been a good year for the Kolb forest. The Kolbs, with volunteer and paid help, have put a significant dent in the invasive plant population in their forest. There’s now a lot less Ailanthus, Oriental bittersweet, garlic mustard, and mile-a-minute vine.

Peter Mehring (whose work was paid for by grant funds from our Foundation) helped attack bittersweet and pretty well exterminated the autumn olive, and Peter’s sons, Ryan and Adam, assisted. Japanese stilt grass will take years to control but with the Kolbs’ daily surges against invasives and their competent, knowledgeable, and industrious helpers, they are optimistic that they can protect native species in their forest.

Foundation by volunteering to remove non-native invasive <br />plants from the Kolb Forest. Shown here holding Japanese Stilt Grass she has just pulled out, Shirley helped Jean Kolb work over this patch last year before it made seed, so that this year there are only a few new plants to pull. Shirley, a member of the Virginia Native Plant Society, has also pulled garlic mustard, mile-a-minute, and other invasive species in the Kolb forest. She volunteers as well with Stream Watch, a group that monitors the health of local streams.

May 2007

For more than a year, the 500-Year Forest Foundation has been mapping sites of previous human activity in the Kolb 500-Year Forest using GPS technology and the owners’ knowledge of historical and natural features.

The often steep terrain in between holds hollows, old apple orchard terraces, remnants of old house sites, and a maturing mixed deciduous forest covering nearly all of the property.

On the lower slopes, an abandoned cabin and the scant remains of a barn mark the site of the earliest farm on the property. An abandoned frame house, higher up and near the western property border, overlooks orchard terraces of a later farm. Upslope from each, rusted iron pipe remnants, former water lines to the dwellings, protrude from the ground. A half-buried barrel, used for mixing calcium carbide and water to produce acetylene gas for light fixtures and a set of kitchen cooking burners, is still in place near a third old house foundation.

August 2006

By Jean Kolb

Back in June, Hal spent a lot of time cutting or pulling Oriental Bittersweet and we’re beginning to see a reduction in the worst places. For most of August, it was too “too darn hot” to be out in the woods doing anything at all. The drought has reduced the stream in the hollow above the house to five very small pools in the exposed bedrock, the least water I’ve observed there in 30 years. It’s too dry to set out more oak seedlings. When it rains and/or the days cool off, we’ll get back in the woods.

On banks and well drained spots, the Stilt Grass is looking deathly dry but, where it grows in low places and has plenty of sun, the Stilt Grass is thick and knee high. After I worked in a really thick patch (to eradicate it) and acquired 21 baby ticks and 29 chiggers on my ankles, I started rethinking my timing. In the past, I left the Stilt Grass (invasive) till later because it blooms so late, but I think I should attack it earlier.

During a cool spell, I re-checked the (Hurricane) Isabel plot and removed the remaining Mile-a-Minute vines left after we’d pulled most of them back in the spring. A fallen tree’s upturned root mass that was engulfed with Mile-a Minute last summer had only one diminished vine on it. A native wild grape was now taking over the root mass.

April 2006

The never-ending efforts to eradicate invasives led to a discussion at the October forest owners luncheon of a fungus that kills Japanese stilt grass. However, forest owner Steve Brooks who made the presentation had to conclude that it’s not as yet a meaningful option in battling the invasive. Similarly, a report in the Foundation newsletter of damage to large trees by wild grapevines prompted an email exchange on the virtues of swinging on vines. Steve said he could safely promise that he wouldn’t eliminate them all. This forest also reported discovery of a huge, 50-pound Hen of the Woods polypore. The owners are also beginning their readiness for a revisit of biotic inventory plots.

Year Long 2015

Tom Dierauf, retired research forester, with the Kolbs assistance, conducted a tree and plant inventory during spring, summer and fall in twelve permanent study plots. In addition the same inventory was recorded in the Natural Heritage plot, bringing it into harmony with the other twelve plots. With this information a conservation plan has been created. The plan calls for the forest to age naturally, invasives to be controlled, and certain trees to be restocked in canopy gaps. The plan is to be reviewed at least every ten years.

September 2004

Phil Coulling, Vegetation Ecologist for the Virginia Natural Heritage Program, visited the Kolb forest in September 2004 and reported that the vegetation consists primarily of mid- to late-successional forest recovering from both timber harvesting in the early 20th century and a wild fire on the south-facing tract in 2001. Two broad community groups are present. Rich cove and slope forests occupy the north-facing parcel, whereas oak/heath forests dominate the south-facing tract.

2019

In June, students from Randolph College conducted an inventory of the property with guidance from their professor, Karin Warren, a 500-Year Forest Foundation director. The inventory work was underwritten by a Randolph College grant. As Karin wrote in the grant proposal, “Each inventory will include tree density, species (native and non-native), abundance of coarse woody debris, scrub, and herbaceous species, diameter, average stand age, and observation/assessment of human disturbance.”

2018

The owner of a 25-acre parcel that adjoins the Sunshine Forest emailed the foundation to say she was “super excited” to learn from her friend Tom Wieboldt that she lived next door to a 500-Year Forest. Tom, a retired curator with the Massey Herbatorium at Virginia Tech, described the mission of the foundation and his work inventorying the Sunshine plants, which included rare finds. The neighbor continued, “This is like a dream come true for me, as I am a tree-lover, and feel strongly that old growth forests are important.”

Summer 2014

The Sunshine Forest has new owners—and they’re Sunshines, too. Ryan and Erica Sunshine have taken over as stewards from Ryan’s parents, Donald and Joanna. This marks the first time a 500-Year Forest has changed owners, making it an historic event not just for the Sunshines, but for the Foundation, as well. Ryan and Erica also have a next generation of Sunshines--son Jeremy and daughter Samantha-- motivating them to continue the family’s conservation tradition.

Tom Wieboldt of the Massey Herbarium at Virginia Tech completed the botanical inventory of the Sunshine forest, producing a list of 221 species. In May, he enlisted help from Natural Heritage Program scientists to install two permanent plots, one on either side of Mill Creek. This winter a report will be prepared detailing the plants.

In addition, he put some concerns to rest for the new owners, reassuring Ryan and Erica that “passing through a plot while hunting or hiking would not be an issue.” He further explained: “Data from thousands of such plots is subjected to rigorous statistical analysis which helps to identify common features in the vegetation and landscape. New data is being added all the time and the classification adjusted accordingly. Plots have been shown to be a good scientific method for studying vegetation and could help the Foundation know how similar or different participating forests are from one another. This could help direct future preservation efforts. It also allows them to put a label or name on what they are preserving that may be useful for communicating with like-minded individuals and provide a crossover with VNHP and other conservation efforts in the state and region.

Fall 2013

Tom Wieboldt, the Virginia Tech botanist associated with the Massey Herbarium, visited this forest twice in 2013. Among his findings: Black-seed ricegrass, a three-parted violet and a lot of Goldies fern. The last of the three was a new record for Montgomery County. In addition to Tom’s efforts, the owners have scheduled the next round of invasives work by Deb and Neil Ames of Neil Ames Horticultural Services for late winter or early spring. That work continues under the invasives initiative announced at the October forest owners luncheon that has the Foundation forgoing the forest owner match and footing 100% of the bill.

September 2011

The Doing In of 3,125 Ailanthus Trees

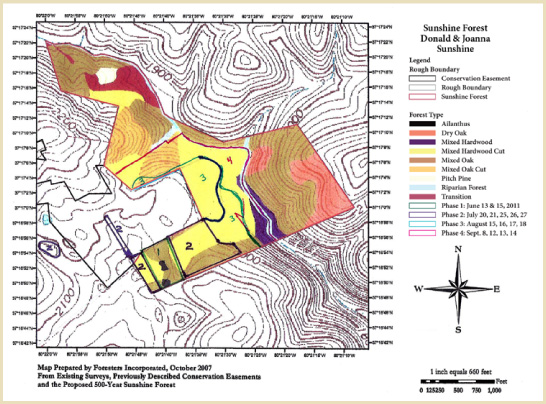

To help us in the understanding of a prospective forest we hire an expert to evaluate its quality as a 500-Year Forest. Our expert was Britt Boucher. In his report he identified some areas that were dominated by Ailanthus also known as Paradise tree or Tree of Heaven, an invasive tree from the China See attached map. Further visual inspection revealed that the forest south west of Mill Creek was also heavily infested with Ailanthus.

This was Donald and Joanna Sunshine’s first year as 500-Year Forest owners. As Donald said, “Thus, began a new adventure.” As reported in the last issue of the news letter, Donald set out to determine with whom he might contract to begin this eradication program. After several tries he was fortunately referred to Neil Ames Horticultural Services.

Neil and Deb, a husband and wife team, were just the right people for this job. In four separate months or phases covering about 50 acres as shown on the map, Neil and Deb worked over the landscape to put to death over 3,000 Ailanthus trees. A similar effort next year should finish off the infected remainder part of the forest. There will be on going effort to control new seedlings in the future.

The Ailanthus tree is either male or female. In some areas of this forest Ailanthus was dominant tree cover. In these places Neil and Deb’s effort was restricted to killing only the female trees opening up the forest to the younger native trees by not exposing the forest floor to full sun

On a very positive note let’s leave this forest with Deb’s observations. “There were also wonderful patches of ferns of all types: Christmas, maidenhair, lady, male, giant wood, ebony spleenwort, walking ferns, and others we couldn't identify. Our walks through the forest have been great horticulture experiences for us. We both grew up spending a lot of time in the woods, and this has been a treat. We hope to continue working with the Foundation in the future.

October forest owners luncheon of a fungus that kills Japanese stilt grass. However, forest owner Steve Brooks who made the presentation had to conclude that it’s not as yet a meaningful option in battling the invasive. Similarly, a report in the Foundation newsletter of damage to large trees by wild grapevines prompted an email exchange on the virtues of swinging on vines. Steve said he could safely promise that he wouldn’t eliminate them all. This forest also reported discovery of a huge, 50-pound Hen of the Woods polypore. The owners are also beginning their readiness for a revisit of biotic inventory plots.

Mid-2010

Joanna Sunshine eloquently expresses her deep environmental concerns. These are “our mountains, our valley, and our forest. We live and work in our farmhouse studios surrounded by the gently rolling, tree covered Blue Ridge. It is a privilege… indeed a gift to live here. We see our task as one of stewards, custodians of the land, of improvement and preservation of the land for generations to come. It is up to us to leave this a better place. We believe no one, no purpose; no cause has the right to destroy nature.” Thus, the Sunshines enthusiastically embraced the idea that their forest could become an old-growth forest.

October 2008

Non-native species, especially Ailanthus, are present and in high numbers in the previously harvested areas. As with much of Virginia, deer are a serious threat to native forest regeneration. Our management efforts will focus on bringing the invasives under control and reestablishing the native forest in those areas. A plan for this work and a detailed analysis of the forest has been developed by Britt Boucher of Foresters, Inc., Blacksburg, Virginia.

Our Foundation received a $3,000 grant from the Virginia Outdoors Foundation and the Virginia Environmental Endowment to conduct a mapping study locating properties already under a conservation easement and with fertile soils in three Virginia counties. The Sunshine property and nine other properties in Montgomery County were identified. The study was conducted under the leadership of Carolyn Copenheaver, Associate Professor of Forest Ecology, Virginia Tech Department of Forestry.